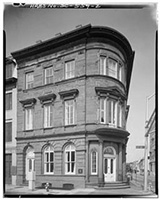

The corner of Broad and East Bay traces its roots to Charleston’s founding and was a prime location from the Carolina colony’s very beginning.

Designated as Lot 13 on the Grand Modell, the site was granted to Jacob Waite in 1680. Waite died in 1690 and part of the lot was acquired in 1696 by wealthy Goose Creek planter, Benjamin Schenckingh who is best remembered for taking part in the peaceful overthrow of the Proprietary government in 1719.

The original two story building at various times housed a watchmaker, grocer, druggist, bookbinder and stationer before becoming a bank.

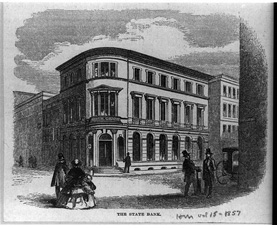

Harper's, Illustration

Harper's, Illustrationof Broad at East Bay

One Broad Street was a modern marvel at the time. The building was designed by Charleston’s most notable antebellum architectural firm, Jones & Lee (Edward C. Jones and Francis D. Lee). This firm designed many local buildings, Magnolia Cemetery and worked elsewhere in South Carolina (including designing the campus layout and Main Hall at Wofford College). When the partnership dissolved in 1857, Lee located his office into One Broad.

Proclaiming the bank’s stature in the business community and enjoying the premier location in Broad Street’s commercial area, the brownstone façade was quarried in Connecticut; each lion head is unique and said to be patterned after bank managers, and its entry doors were faux-grained mahogany with cast iron grills. The interior was equally impressive and catered to the tastes of the luxury-loving Charleston elite.

Book Cover Found in Wall

Book Cover Found in Wall

Cannonball hole

Cannonball holeuncovered in 2015

The bank relocated the business but didn’t escape a bad fate as its Blue Ridge Railroad Company Bonds

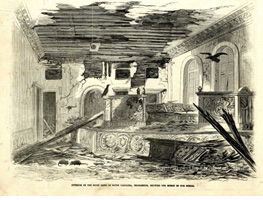

Banking Hall Shelling Damage,

Banking Hall Shelling Damage,Leslie's 1865 Illustration

The bank’s architects fared better. During the war, Jones was attached to the commissary of the Regiment of Reserves in 1861. In 1866, he moved to Memphis, where he had a second career designing numerous landmarks in Tennessee, Mississippi, and elsewhere in the south. Where Jones’ early buildings were produced with sixteenth century techniques and tools, by 1890 he had mastered steel and rivets, thus enabling him to produce the first skyscraper in Memphis, which still stands today. One of his churches later became Clayborn Temple, where the 1960’s civil rights sanitation worker marches started and ended, and Martin Luther King spoke several times. Jones died in Memphis in 1902.

Lee's Wrecked Torpedo Boat David

Lee's Wrecked Torpedo Boat David

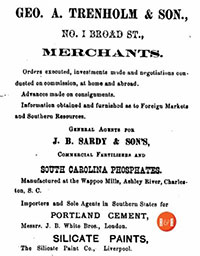

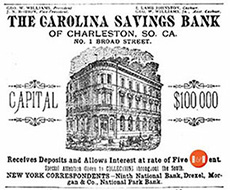

In 1866 the damaged building was sold to partners of Fraser, Trenholm and Company which was the company led by George A Trenholm, one-time Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederate States of America.

Trenholm and his firm were a leading, cotton brokerage, shipping,

G.A.Trenholm

G.A.Trenholm

In 1876, the second floor of One Broad Street was used as an armory for the Carolina Rifle Battalion, which was a large Charleston-based militia group associated with the Red Shirts of Democratic Party gubernatorial candidate Wade Hampton III. Hampton’s win marked the end of Reconstruction (4) and the military occupation of South Carolina. In 1879, three years after Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone, the second floor of One Broad Street became the first telephone exchange in South Carolina and the telephone exchange eventually took over the whole floor.

From 1877 until 1897, the top floor was occupied by the local office of U.S. Signal Corps (and its offshoot, the U.S. Weather Bureau) . On August 31, 1886, an earthquake destroyed much of Charleston; One Broad Street survived and its repair was supervised by the U.S. Signal Corp.

Earthquake Rod "Spider Web" Design.

Earthquake Rod "Spider Web" Design.

The three layers of stabilizing rods were revealed during the 2016 restoration. Mark Dillion, a structural engineer working on the building remarked that “the tension rod system in One Broad is the most elegant and comprehensive I have seen in my 32-year career and the roof rod design closely approximates what modern earthquake engineering design is supposed to do.”

In 1948 Carolina Savings Bank did an update of the building. Simons and Lapham architects gave the banking hall a contemporary mid-century look by lowering the door heights, simplifying the trim details and opening up the decorative alcove with a modern steel vault door with entry to the vault directly from the main room. (5) The building was air conditioned, new stairs and a fireproof records vault were added to the 2nd floor for the bank’s bookkeeping department’s relocation. Since it never floods, the basement was turned into a storage area for cancelled and live checks and bank forms.

Carolina Savings Bank owned and operated from One Broad Street for 82 years. Prior to its 1948 renovation, the bank leased out the upper floors to various tenants. One of the more prominent companies whose headquarters were located on the 2nd and 3rd floor from 1912 through 1930 was Carolina Portland Cement Company. (6) Hanahan, SC is named after the company’s president, J. Ross Hanahan, who was also a founder of the Charleston Water System. Mr. Hanahan’s company established several chemical and phosphate fertilizer plants in Charleston’s Neck Area, and the environmental cleanup is still being litigated today. Other tenants included Magnolia Cemetery’s office, the French Consular Agency, law offices, real estate agents, foresters, engineers and a public stenographer.

In 1957 Carolina Savings Bank was sold to First National Bank of South Carolina of Columbia and the vacated building was sold to an Irving, Melvin, Klyde and Rudolph Robison family partnership. The building was leased for a short while by SCN Bank and the Federal District Court. Carolina Bank and Trust moved into the building to use as its main office in 1963 and in 1968 they purchased the building from the Robison partnership. One year later, Bankers Trust of South Carolina purchased Carolina Bank and Trust and One Broad Street.

In 1978 Bankers Trust carried out a $320,000 restoration of the building. The contractor for the work was Frisch Construction Company. The exterior was in very poor condition due to moisture penetration, freezing and cracking; the brownstone was flaking and failing onto the street.

1960's photo showing brownstone flaking

1960's photo showing brownstone flaking

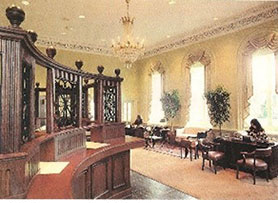

1980 renovated interior

1980 renovated interior

In 1985 Bankers Trust was acquired by NCNB (North Carolina National Bank) which became Bank of America.

In 1993, NCNB vacated and sold the building to investor Helen Bradham who sold the building to One Broad Street LLC in 1998. During this time, Carolina First Bank of Greenville, SC used the location for its downtown branch in Charleston. In 2004 the building was sold to Broad Street Ventures, LLC and in 2006 Carolina First Bank (now called TD Bank) vacated the building because it was obsolete for lack of a convenient drive through. The interior was stripped and plans were made to convert its use to luxury condominiums. Unfortunately, the conversion plan was upended by the Great Recession of 2007, and the building has been vacant ever since.

Recently, there’s new life at Broad and East Bay. In 2015, The building was purchased by Mark Beck, the founder of a multinational business technology firm based in Mooresville, NC. Mr. Beck restores historic buildings as a hobby and he and his team, made up of Charleston-based architect Bill Huey and Associates and contractor NBM, took the interior back to its 1853 appearance with original door heights, restored decorative plaster, encaustic floor tile imported from England and period Cornelius and Baker gasoliers (restored for LED lights). The space is adapted for mixed use with retail on the first, office on the second and an apartment on the third floor. The exterior was patched to retain as much of the original finish as possible, the windows and sashes were repaired, reglazed and painted their original dark green color.

“One Broad Street is totally modern underneath—all new energy efficient mechanicals, plumbing, fiber, security and fire safety—carefully hidden inside the original fabric of a truly spectacular 1853 building” Beck says.

In the restoration, some of the old has returned, but in new ways. One item Beck located and purchased is a never-circulated 1861 printer’s proof for the State Bank of South Carolina’s $5 note that features a picture of the building. He commissioned a dimensional artist to photograph, print and twist the image into an original 6 x 4-foot acrylic artwork, which can be seen in the Alley Way entrance on Broad Street.

Special thanks to Peg Eastman for her tremendous insight and research that contributed so much to this information. Her article Rescuing One Broad Street, Part I and II was published in the Charleston Mercury, January and February 2016 editions and One Broad Street: Architectural Gem in the South Carolina Historical Society Carologue Summer 2016, Vol. 32, No. 1 edition.

- State Bank of South Carolina History

- Edward C. Jones

- Jones, Edward C. (1822-1902)

- Edward Culliatt Jones

- Edward C. Jones, the architect of Main Building

- Lowcountry Digital Library

- Magnolia Cemetery

- Magnolia Cemetery

- Mercantile Library of Cincinnati

- 654 MERCANTILE LIBRARY OF CHARLESTON

- Magnolia Cemetery

- A history of banking in the United States

- To the Sound of the Guns

- George Trenholm

- George Alfred Trenholm

- The Real Rhett Butler Revealed

- Confederate gold

- South Carolina - The 1800s

- Calhoun Mansion

- Hampton and his Red shirts

- The Birth of a Modern Water System

- Great Recession

- Bridgetree

- History of Banking in South Carolina from 1712 to 1900 By George Walton Williams, George Sherwood Dickerman

- U.S.A. Banknotes Miscellaneous Currency

- The Sebrings:Information about Edward Sebring

- Page 112, Hampton and His Red Shirts; South Carolina’s Deliverance in 1876 by Afred Brockenbrough Williams, 1856-1930.

- Architectural Drawings of Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham

- Moody's Manual of Investments: American and Foreign, Volume 13, Issue 2; edited by John Sherman Porter

Authors and historians Peg Eastman and Robert Stockton contributed to this information

- HABS No. 1 Broad St. SC-559 • Charleston Historic District, National Register # 66000964, 1966 • declared National Historic Landmark District, 1960

- Stockton, DYKYC, June 25, 1979.

- Charleston Daily Courier, March 7, 1853;

- Bergeron, passim; Stoney, This is Charleston, p. 10; Ravenel, Architects, p. 212, 214; Mazyck & Waddell, illus. p. 59; Simms, "Charleston, The Palmetto City"; Severens, "Architectural Taste", p. 6; Green, unpub. notes, HCF

- The History of the Banking Institutions Organized in South Carolina Prior to 1860 by Washington Augustus Clark

- A History of Banking in the United States by John Jay Knox

- Harper's New Monthly Magazine Volume 0015 Issue 85 (June 1857), Title: Charleston, The Palmetto City

- Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820-1920, By Paul S. BOYER, Paul S Boye

- Treasures of the Confederate Coast: The 'Real Rhett Butler' & Other Revelations Paperback – January 1, 1995 by Edward Lee Spence

- Neck Area redevelopment: A tale of arsenic and old money plays out in a Charleston courtroom, David Slade, The Post and Courier, August 19, 2014

-

No comment found